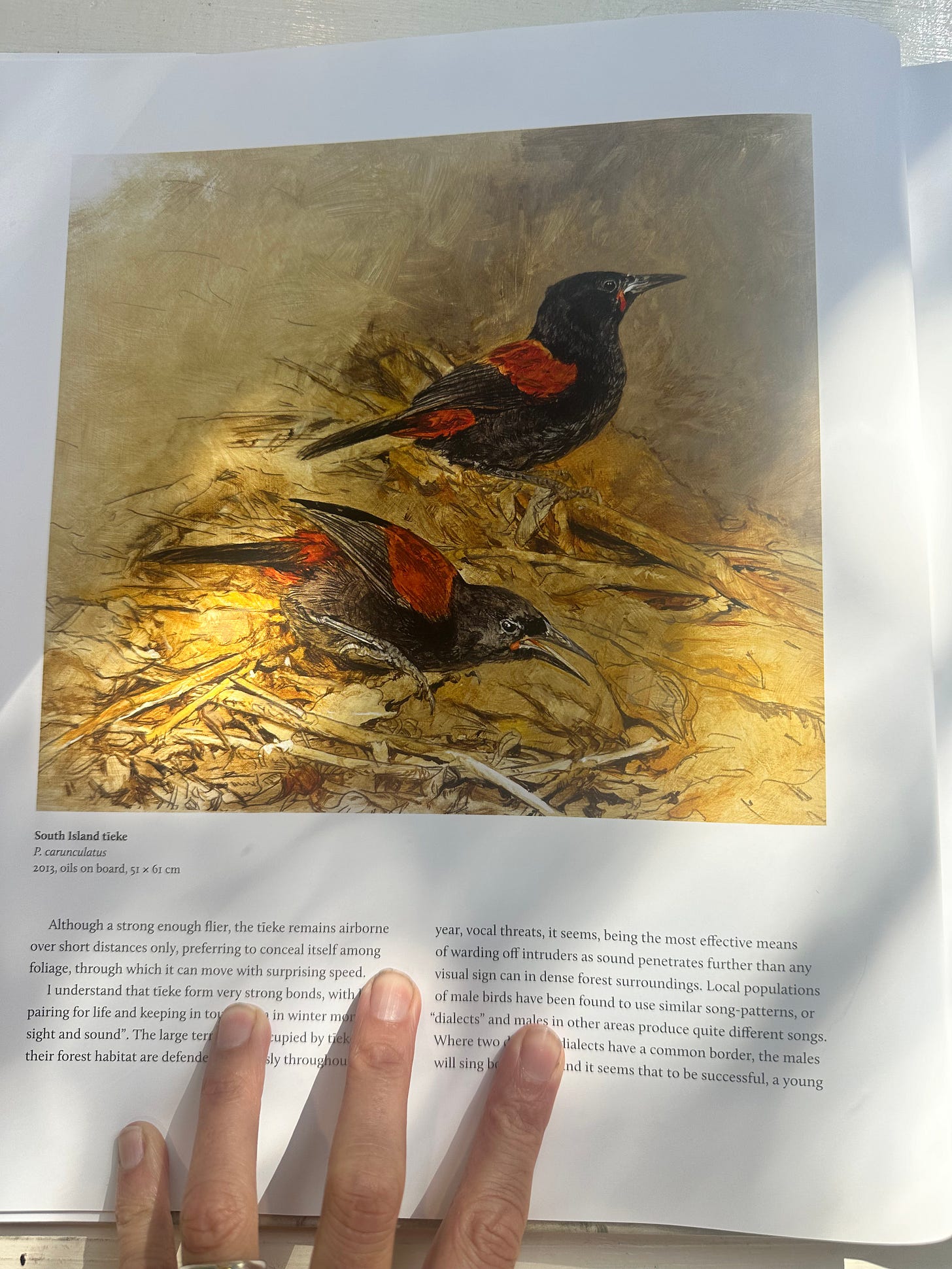

Welcome! I’m so glad that you are here. In this piece I use two names interchangeably: Tīeke & Saddleback. Both refer to the beautiful South Island Saddleback, a bird endemic to the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand. Tīeke is their Te Re Māori name, referring to their high pitched, laugh-like call. ‘Saddleback’ is their english name that references their band of orange plumage.

My home is not the place that I was born to, but the one that I was called to. A small, grey plane carrying a wide-eyed, youthful traveler bound for the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand some twenty-years-and-then-some time ago.

Plane wheels on the ground, bump.

A body that is restless, unsettled, searching, bump.

A mind confused and weary, bump.

Landed, grounded, home.

I cancel all return tickets, understanding instantly that the soil beneath me beds my tap root. Feet on the ground, the arboreal spine of the Rimu supports me, the birdsong of the Tūī guides me forward. This is the land I choose to serve, the place I choose to stay.

Home: where my desires and beliefs have found their form, where my voice and words weave their way to understanding.

I am familiar, familial, returned, even if all logic cannot define exactly why.

But what is home, if not intuited? What is home, if not chosen? What is home, if not complicated?

“If tīeke, the saddleback, would sit still for just long enough, its splendid chestnut and black colouring and to the artist’s eye, quite perfect proportions, I would have it as the first to paint of all our birds. As it is, I am driven mad by its never ending zip zipping about the forest floor.”- Ray Ching

This last few days, Tīeke, or the Saddleback, a native New Zealand bird, has been (re)introduced to our local ecosanctuary. I have long been enamoured by the Saddleback, despite never having seen one in person. As it stands, our relationship thus far is solely imagined, existing with a realness I can touch.

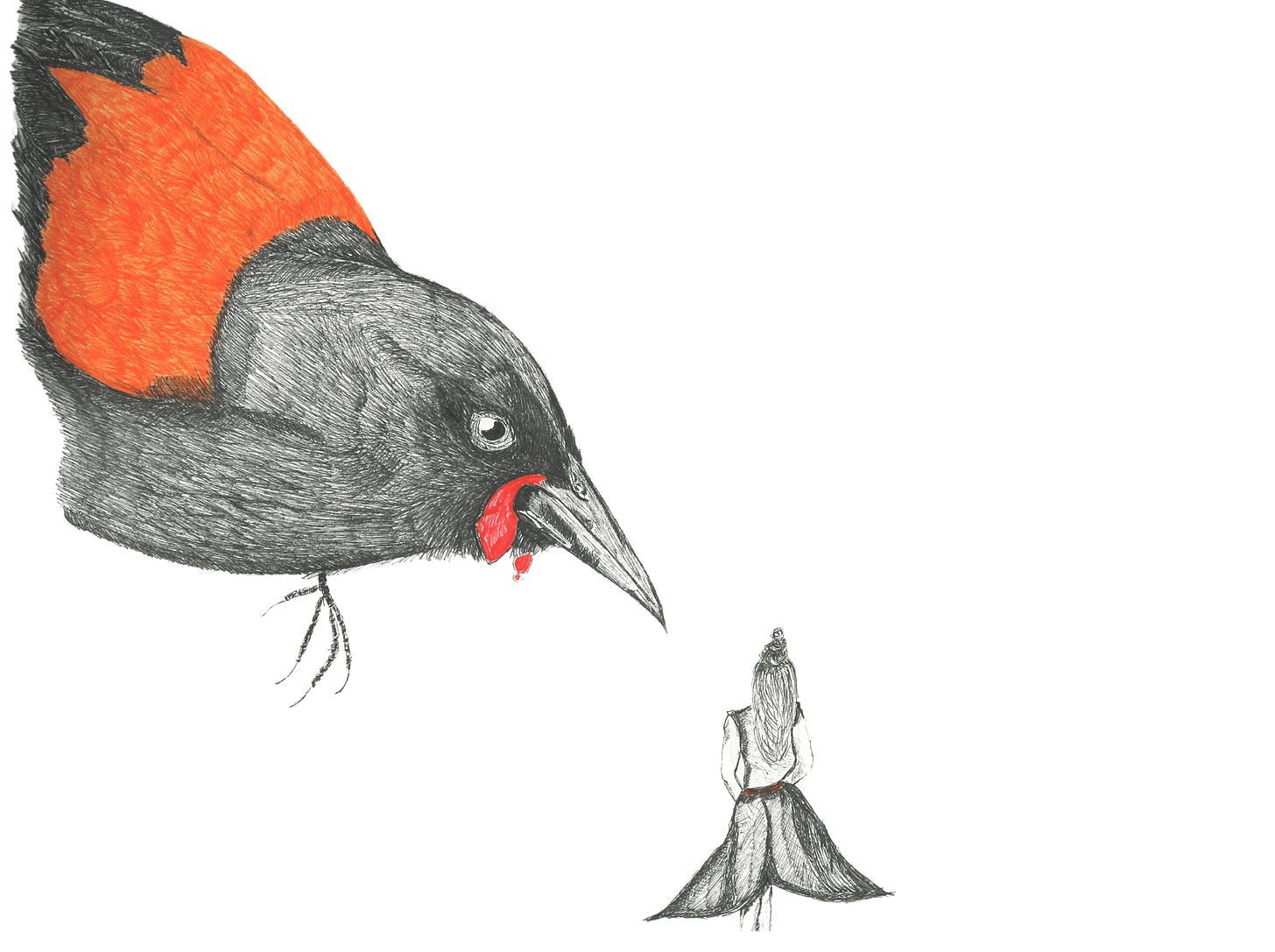

A little while back, I began creating what I came to call my Book of Allies, a ritual magicked into existence to sustain me through a difficult time. The practice works like this: each morning when I wake up, I hop skip my way around the usual temptations that call out from the confines of my phone. Instead, I take out my sketchbook with the soft blue cover, my favourite black ink pen and start to draw. I would draw whatever or whomever comes to mind, intuitively, instinctively. At first, I was worried that no-one or nothing would arrive, that I would sit blank paged and equally blank of mind-- but they always did. And always the birds.

Pen in hand, I watched my allies find me, arriving in fine lines of changing grip and pressure, amidst a myriad of tensions and uncertainties, each stroke alerting me to an undercurrent of mood or feeling that would have otherwise passed me by. As I grew their images on the page, the anxious parts of me became diminished. My Book of Allies could equally be called my Book of A Thousand Tiny Exhalations.

Tīeke become a talisman, an ally, that accompanied me in my thoughts and dreams, popping up all over. Gifts given to me by people unintentionally contained images of Saddlebacks, despite not having mentioned them or told them of my early morning drawings. I went to buy a doormat- randomly- and was told they only had one left. I laughed when I saw it embossed with my black and tan birds. Another time, sitting in my chair in my office, feeling flat and unenthused, my husband approached, holding a letter in his hand and waving. I open it and read the words inside:

Saw this and just had to send it to you.

The illustration on the card: Saddlebacks.

I began to talk to them, expect them, reach out to them. With them, I understood friendship and support differently. We have many natural allies in the world, beyond what we logically understand and recognise. Seeing and creating is a kind of opening; it makes us available for the things we need to find us.

When I first learned of the release of the Saddlebacks at the ecosanctuary next door, I shot back in my chair and let out squeals. Their presence in this moment is both significant and sacred; the return of something lost, the repair of something damaged, the hope of what is possible to restore.

Imagine: Some 80 million years ago, the landmass that was to become Aotearoa New Zealand split from Gondwana land and floated her own way, a sliver of vibrant green coming to rest in the lively waters of the Pacific. With the absence of land based mammals save for bats, the bird life that evolved here was primarily ground dwelling, ground loving, or even flightless; in the face of introduced predators, they are both literal and metaphorical sitting prey.

Saddlebacks, whose song once echoed throughout the forests of the South Island, fell close to extinction by the end of the 20th century, a combination of colonisation, forest clearing and predation by introduced animals such as ship rats, cats and stoats. Reduced to a presence only on three remote islands off the bottom tip, the mainland was left to hold them only in longing and in memory.

And yet still, things went from bad to worse. In the 1960’s their survival on these secluded isles too became imperilled; rats brought ashore by a visiting boat spread to all three areas of land causing various other species to become extinct, and putting the Saddlebacks at very real risk of being wiped out completely.

The conservation effort to save the Saddlebacks was the first successful translocation to save a species anywhere in the world (I thank those people daily); the current population of two thousand birds is descended from the survivors of the 36 Saddlebacks rescued in 1964.

36 and now there are 2,000.

I hold these numbers close:

36 is another word for hope.

I push open the stiff glass doors and make my way into the high-ceilinged lobby of the ecosanctuary. I feel self-conscious, despite this being a place I love and have visited countless times. As the crow flies, I live directly next door, separated only by a mountain, and a wide band of trees; this is ground I know and yet I enter as though it’s my first time.

I do not wish to talk; not to the people at the desk, not to anyone inside. I become, oddly, overtly aware of my humanness. Knowing myself to be within the zone of the Tīeke, I am reverent, reminded of a universe that’s fluid and volatile, brutal and beautiful. I feel I am traversing a thin place; a presence fills me that reminds me once again I am mortal.

I wonder of Tīeke, of the memory that’s stored within their body. Of the stories and desire lines of the original 36 carried in the clay of their bones.

Does their song sing the notes of those they lost? Is their chorus now a keen?

In that moment, lost in thought, communication seems to fail me.

The words that find me are insufficient, do not arrive complete.

“Are you hoping to see the Saddlebacks?” I am asked.

“Yes,” is all that I reply.

I take the piece of paper with the number of the door code, slip away and head across to locked sanctuary enclosure door outside.

Does the Tūī decide? Does the Eel get to have a say? Where does the sound of the Saddleback fit within the delicate symphony of the valley? Does she grieve, for where she left? Does she celebrate, for where she’s come to stay?

What is home, if not complicated?

I enter through the grey steel sanctuary gates. I am thinking of disturbance; of what it means to settle somewhere new, what it means to feel “at home”.

There is a horse that lives above us on the hill, and with the exception of a few months a couple of years back when he had a temporary friend, he has always lived alone. Every time I see him out my kitchen window I feel a sadness. Horses are herd creatures; their sense of safety and sanity is predicated on the presence of their bandmates. Between them, rest and alertness is negotiated and shared round. Understandings of both the environment and themselves is filtered through the lens of the whole herd. Isolation is not only unnatural, but fundamentally unkind. It can only result in anxiety or shutdown.

His paddock rests at the top lip of the valley; above him to the north lives a herd of three. Below him, down the dip and to the south, a herd of seven. He stands at the hinge point in the middle. Our land- and my view outside the kitchen window- oversees the whole domain and I watch him respond, move in relationship to the horses either side.

I witness him include his distant kinfolk in their far off paddocks within his energetic zone. If a horse on the hill leaves, or disappears from out of sight, he will call out. If there is disturbance or shenanigans in the fields down below, he frolics also.

He has made a space for himself, a herd for himself beyond the fence lines and falsities of ownership—an insufficient one, but the only one he has. They call to each other, speak, but not in ways that we can hear. They move, together but apart.

As I walk now in the sanctuary, I think of the horses and their awareness of each other’s positioning and presence; each individual member to each other, each group to the other. As humans, within the solid walls we have created for ourselves, our sense of relationship is flawed. We can live for many years without awareness of our neighbours, without ever understanding or truly seeing the tidal flow of presence, of emotion, of change that is a constant all around us.

I consider the sound ecology of the sanctuary, how each bird, creature within the ecosystem here has a tune specific to their niche. When I step into the forest, I hear the song of the Tūī, the sonorous, whooshing wings of the Kēreru, the whistle chirping of the frogs, a soundscape we refer to as biophony. Biophony is the term used to describe the collective vocalisations, or signatures, of all sound producing creatures (except the human). In a harmonious ecosystem, each being has their own sound signature, their own frequency and vibration that neither competes with nor cancels out anyone around. In this way, communication between each other is ensured, and their collective music forms a symphony that becomes the acoustic imprint of that particular patch or place.

I wonder to myself where the song of the Saddleback fits in the soundscape of this place, their now-new home. Was their place in the symphony always ensured, always saved?

I wander the ecosanctuary tracks, aware of my footfalls, how the presence of my body creates its own disturbance. To my right, I see a South Island Robin flit within the trees. I pause, bend my knees and crouch down in the gravel. Kakaruai (the Te Reo Māori name for South Island Robin) is a charmer; their eye contact, the way they move towards you instead of away makes it easy to convince yourself they’re here for conversation. They flatter you enough to let you entertain the thought they really like you.

Plus, they are fairy tale level cute. Long, supermodel legs springing them around; in their presence joy bubbles to the top.

Kakaruai are another sanctuary member who are slowly making a much yearned for reappearance. Rarely seen outside the protected walls, inside they bounce within the undergrowth and frequently appear above you in the trees.

I speak out loud to my enchanting robin friend.

“How do you feel?” I ask him.

I wonder:

What he felt when first song of the Saddlebacks physically touched him. A body that has never been in the presence of such a bird- not in his lived lifetime now at least- and yet a shared ancestry extending back to times of thriving my imagination can barely contain.

Was there a moment, a pause, when he felt the air was snagged with sound?

Did his wings find an extra beat, release a discharge of energy, a celebration, a cellular remembering?

What is home, if not complicated?

On this day, I do not see the Saddleback, and in truth, I don’t expect to. To be in this place, with the knowledge they are here, for now feels quite enough.

What’s more, theirs is a disobedience I encourage; they owe us humans nothing. As is true of all wild things, they belong only to themselves.

Their story and re-arrival has gifted me with questions:

Of our responsibilities for protection. Of what is required for mutual healing. Of what we are being called towards and beyond.

To my right: the sound of wings. The Bellbird tracks behind the flight path of the Tūī, her wings an airborne moss, swiftly blending into the background, out of sight of eyes not specific in their focus.

Their message lands inside my mind:

“Close your eyes,” they say. “Hear what is offered- differently.”

Thank you so much for reading 🪶

xx Jane

I was also honoured to be a guest on my wonderful friend

‘s podcast. If you want to listen to our conversation on all things creativity and the deeper layers of our creative and artistic journeys, you can do so here 🪶Ongoing admiration and support to Orokonui Ecosanctuary for their love and care of our native wildlings (and whose collaborative work has seen the return of precious Tīeke). You can learn more Orokonui or find out how you can support them here.

Jane, this is incredible. Welcome home to the Saddleback. And to you.

Such a lovely story. Felt happy for this to be my “global news” today. We are kin.